Introduction

In the last lesson, we learned how neural networks can apply a series of transformations on some input data in order to eventually produce a final prediction. This process of transforming the input data by feeding it through layers of artificial neurons, of each of which applies its own weights, biases, and activation functions, is known as “Forward Propagation.”

However, you’ll note that we never actually went through our training data and used it to train our model parameters (i.e. the neuron weights and biases). As a result, the transformations that were being applied to the input data were pretty much random, since we randomly initiated the weights and biases. As you could probably predict, this would mean that our final output would be more or less random as well.

In this lesson, you’ll see how we can start from this random initialization, use a cost function to measure just how bad our predictions are, and gradually train our network to make more and more meaningful predictions via gradient descent. However, since these neural networks have more than one layer, you’ll see that we have to do some extra work in order to calculate these gradient terms for our model parameters.

Once we’ve gone through the work of training out network, the end result will be a flexible model that is capable of learning even more complex relationships within data than linear regression or logistic regression.

Gradient Descent

To see how exactly we can train neural networks to make predictions that match the training data, we’ll continue with the familiar example of handwritten digit classification. Let’s start off with a video discussing some ideas that should feel pretty familiar to you from earlier lessons: cost functions and gradient descent.

Just like we did in linear regression, we’ll set up a cost function that will measure just how bad (costly) our predictions are. This will primarily be a function of our model parameters (weights and biases), since we can get different cost values by changing our parameters. When we say that we are “training a network,” we really mean that we finding the parameters that minimize our cost function.

To do this, we will use gradient descent to find out how, given our current parameter values, we can tweak our parameters so that we reduce our overall cost. Just as before, we will repeatedly apply these gradient descent steps until we converge on our optimal parameters.

Backpropagation

Next, we’ll see how to actually calculate our gradient terms so that we know which way to move our parameters. While this was relatively straightforward in linear regression, it will take some more work when it comes to multi-layer neural networks. Let’s first explore the intuition behind this process, known as Backpropagation.

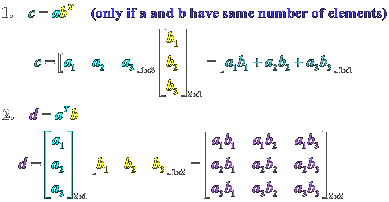

Now that we’ve explored the idea of Backpropagation in general, let’s dive into the math behind it. The next video may be a little symbol heavy, so it will likely be helpful to think about what each symbol actually means in English. Here are some good starting points to get your feet planted:

- \(W^{(i)}\) is the weight matrix used by the \(i\)th layer in the network. These are the parameters that we eventually want to be able to optimize.

- \(z^{(i)}\) is a vector containing the weighted sums of the inputs (and bias terms) of the neurons in the \(i\)th layer. This term directly depends on the weights of this layer, since these weights will dictate the value of the weighted sum.

- \(a^{(i)}\) is a vector containing the activations of the neurons of the \(i\)th layer, and is equal to the weighted sum of the layer after passing it through the activation function. This term directly depends on the weighted sum \(z^{(i)}\).

- And a new one: \(\frac{\partial C}{\partial z^{(i)}}\) is a vector representing the “error” of each of the individual neurons in the \(i\)th layer. Here, \(z^{(i)}\) is the weighted sum of the neurons within layer in question. This tells us which way we should try to shift the weighted sum of any one neuron in the given layer in order to decrease our final cost \(C\).

We will start by finding the error terms at the right-most end of the network (the neurons closest to the output), and then use the (multivariate) chain rule to propagate this error back through the previous layers until we calculated have the gradient terms for all our model weights. You can think of this process as tracking how changing one neuron’s weight somewhere in the network affects that neuron’s activation, which in turn affects all the next layer’s activations (since they all take in all the previous layer’s activations as inputs), which eventually affects the final cost. We want to find out how we can change that one weight so that it shifts the following layers’ activations in a way that reduces our final cost.

In order to actually calculate our gradient terms \(\frac{\partial C}{\partial w_{ij}}\), we need to be pretty clever in the way that we track how changing one weight anywhere in the network ends up affecting the final cost. To do this, we’ll work our way backward through the network: we’ll start by calculating the error terms at the neurons closest to the output, and then keep propagating this error through to the earlier layers. (This will require us to apply the chain rule a pretty absurd number of times.) Along the way, we’ll see which weights are responsible for most of the error in the network, and then adjust their gradient terms accordingly.

As we propagate the error backward, we’ll eventually begin to reveal which way we should change the weights early on in our network so that they change the subsequent activations in a positive way (that is, in a way that reduces our final cost). Once we have all our gradient terms calculated, we’ll finally know which way to apply our gradient descent step so that we end up decreasing our cost function, and making our predictions just a little more accurate.

In case this has you lost, don’t worry. Almost everyone feels lost when they learn about backpropagation the first couple times around. If you’d like to try looking at another source, check out this section on backpropagation from Mike Nielson’s online book, Neural Networks and Deep Learning. You may find his explanations more intuitive than most.

Backpropagation: Written Explanation

The example in the video was only for a two layer network. Here, we will generalize the backpropagation algorithm to an arbitrary neural network.

Below, we will go through the basic equations behind backpropagation.

For the simplicity's sake, we'll assume that the activation function is the

same throughout the entire network. However, you should see that this could

easily be generalized to different activation functions for each layer.

Let's say that we have a neural network with \(\textbf{L}\) layers, input \(\textbf{x}\) and a single activation function \( f \) that is used by each layer.

In this example, we will use \( J \) to denote the overall cost of the network, and \( \delta \) to refer to the "error" of a given neuron. For any individual neuron, this error term tells us how changing the weighted sum of the neuron (\( z \)) changes the overall cost. Since each layer we're dealing with will have multiple neurons, we'll use \( \delta^m \) as a vector to represent the error terms of each

of the neurons in the \( m \)th layer.

(In some other textbooks/resources, you may see these error

terms referred to as "sensitivities", and notated with \( s^m \). As seen above, the overall cost may also be denoted using \( C \))

Recall these basic equations that we use for forward propagation:

$$

\textbf{a}^{0} = \textbf{x} \text{ (Starting with the input layer)}

$$

$$

\textbf{z}^{m+1} = \textbf{W}^{m+1}\textbf{a}^{m} + \textbf{b}^{m+1}

\text{ (Computing the weighted sum from any one layer to the next)}

$$

$$

\textbf{a}^{m+1} = f(\textbf{z}^{m+1})

\text{ (Passing the weighted sum through an activation function)}

$$

$$

\textbf{a} = \textbf{a}^{L}

\text{ (Using the output of the last layer as out final output)}

$$

Given this output, let's backpropogate the error terms to adjust the

parameters of the network based

on the expected output. Since changes in the earlier layers

will subsequently affect all later layers, we'll have to use the chain rule to

work backward from the final (output) layer to the earlier layers.

Starting at the End

To compute the error of the neurons in the final layer, we use the chain rule to calculate:

$$

\delta^{L} = \frac{\partial J}{\partial \textbf{Z}^L} =

\frac{\partial \textbf{a}^L}{\partial \textbf{Z}^L} \frac{\partial J}{\partial \textbf{a}^L} =

f'(\textbf{z}^L) * \frac{\partial J}{\partial \textbf{a}}

$$

(Both \(f'(\textbf{z}^L)\) and \(\frac{\partial J}{\partial \textbf{a}}\) are n-dimensional vectors, so we perform

an element-wise multiplication on these

vectors, i.e. multiply each element in one vector

with the corresponding element in the other, rather

than a matrix multiplication. The end result

is another n-dimensional vector that represents \(\delta^{L}\).)

Basically, what we've done here is start with the final layer's

error terms that we want to calculate, and plug in our definition of "error" (partial derivative of the cost with respect to each neuron's weighted sum, or \(\frac{\partial J}{\partial \textbf{Z}^L}\)). Then, since the output neurons' weighted sums affect their activations, which in turn affect the final cost, we chain-rule out this partial derivative to get a product

of two related terms: the partial derivative of the output activations with respect to the final layer's weighted sums \(\frac{\partial \textbf{a}^L}{\partial \textbf{Z}^L}\), and the partial derivative of the cost with respect to the final activations (i.e. our final predictions) \(\frac{\partial J}{\partial \textbf{a}^L}\).

Since we know that the final activation is a direct function of the inputted weighted-sum (given by the activation function \(f(\textbf{z}^L)\)), we can substitute in \(f'(\textbf{z}^L) = \frac{\partial f}{\partial \text{z}^m} \) for the former term in the chain-rule product. In this equation, \(f'(\textbf{z}^L) = \frac{\partial f}{\partial \text{z}^m} \), or the derivative of the activation function with respect to its input (i.e. the weighted sum). If we use the sigmoid

activation function, then this term will equal the slope of the sigmoid graph at our

current pre-activation weighted sum.

The way we evaluate the last term (\(\frac{\partial J}{\partial \textbf{a}^L}\)) will depend on what specific cost function we use,

but since the cost function is already written in terms of the final

predicted values (to see how far off they are from the actual values), it should be easy

enough to differentiate the cost function with respect to our

prediction, just as we did in the previous linear/logistic regression lessons. For the mean-squared error cost function, for example,

this will involve using the power rule to move the "squared" exponent

to the front of the expression.

Working our way Backward

Then, we have to backpropagate this error to all the earlier layers.

The main challenge here is to write out the error of one layer (\( \delta^m \)) in terms of the

error of the next layer (\( \delta^{m+1} \)). Once we have this relationship, we can start

working backward through the network to infer how changing the

weights of one layer early on in the network will trickle down through

all the layers of the network, and eventually affect the final cost.

We can write out the error terms of the \(m\)th layer's neurons as follows:

$$

\delta^{m} = \frac{\partial J}{\partial \textbf{z}^m} =

\frac{\partial \textbf{a}^m}{\partial \textbf{z}^m} \frac{\partial \textbf{z}^{m+1}}{\partial \textbf{a}^m}

\frac{\partial J}{\partial \textbf{z}^{m+1}} =

f'(\textbf{z}^{m}) * \left( \textbf{W}^{m + 1} \right)^{T}

\delta^{m+1}

$$

(Both \(f'(\textbf{z}^{m})\) and \(\left( \textbf{W}^{m + 1} \right)^{T}

\delta^{m+1}\) are n-dimensional vectors, so we perform

an element-wise multiplication on these

vectors, i.e. multiply each element in one vector

with the corresponding element in the other, rather

than a matrix multiplication. The end result

is another n-dimensional vector that represents \(\delta^{m}\).)

Again, what we've done here is start with the current layer's

error terms that we wish to calculate, and plug in our definition of "error" (partial derivative of the cost with respect to each neuron's weighted sum, or \(\frac{\partial J}{\partial \textbf{z}^m}\)).

Then, since this layer's weighted sums affect this layer's activations, which in turn affects the next layer's weighted sums and activations (because the next layer's neurons take in this layer's activations as inputs), which in turn eventually affect the final cost, we chain-rule out this partial derivative to get a product

of three related terms:

the partial derivative of the current layer's activations with respect to the current layer's weighted sums (\(\frac{\partial \textbf{a}^m}{\partial \textbf{Z}^m}\)), the partial derivative of the next layer's weighted-sums with respect to the current layer's activations (\(\frac{\partial \textbf{z}^{m+1}}{\partial \textbf{a}^m}\)), and the partial derivative of the final cost with respect to the next layer's weighted-sums (\(\frac{\partial J}{\partial \textbf{z}^{m+1}}\)).

Just like we did last time, we can re-write each of these three

terms based on what each of them represents. The first term represents

how quickly this layer's activations change with respect to its weighted-sums, which already know is given by the derivative of the activation function, \(f'(\textbf{z}^{m})\). The second term

represents how changes in this layer's activations affect

the next layer's weighted-sums. Since we know that

the weighted sums are of the form \(\textbf{z}^{m+1} = \textbf{W}^{m+1} \textbf{a}^{m} + \textbf{b}^{m+1}\), this partial derivative turns out

to be equal to the weight matrix \(\textbf{W}^{m + 1}\). (If you're familiar with the rules of differentiation,

you can think of \(\textbf{W}^{m + 1}\) as the "coefficient" for \(\textbf{a}^{m}\). We then apply a transpose to make the dimensions match up for the matrix multiplication.)

Then, we can notice that the third and final term

is by definition equal to the error of the next layer's neurons, so we plug

in \(\delta^{m+1}\) and call it a day.

To work backward through the network, we start by calculating the

error terms of the rightmost layer, and then progressively plugging

in for \(\delta^{m+1}\) and

repeating these error calculations for \( m = L - 1 \) to \( m = 0 \),

until we have finally calculated the error terms for every layer in the network.

Calculating the Gradients

Then, to get from the error to the actual gradient (i.e. the partial derivative of the final cost with respect to the weights) in a given layer, we can take: $$ \frac{\partial J}{\partial \textbf{W}^{m}} = \frac{\partial J}{\partial \textbf{z}^{m}} \frac{\partial \textbf{z}^m}{\partial \textbf{W}^{m}} = \delta^{m} (\textbf{a}^{m-1})^{T} $$ Notice that the first term in the chain-rule product is, by definition, the error of the neurons in the \(m\)th layer, and that the second term is the partial derivative of the given layer's weighted-sum with respect to its weights. Since \(\textbf{z}^{m} = \textbf{W}^{m} \textbf{a}^{m-1} + \textbf{b}^{m}\), this second partial derivative evaluates to \(\textbf{a}^{m-1}\). Since \(\delta^{m}\) and \((\textbf{a}^{m-1})^{T}\) are both column vectors, we once again apply a transpose to make the dimensions match up for the vector multiplication. The result will be an (m x n) matrix whose dimensions match up with the given layer's weight matrix.

(In the case of the first layer in the network, \(\textbf{a}^{m-1}\) will be the input vector \(\textbf{X}\), because the weighted sum will be a function of the input features instead of a previous layer's activations.)

Applying Gradient Descent

Using these error terms, we can now update the parameters of the network. We'll use \( \alpha \) as our learning rate to control how quickly we descend our gradient, and \( k \) to denote our current gradient descent iteration. $$ \textbf{W}^{m}(k+1) = \textbf{W}^{m}(k) - \alpha \delta^{m} (\textbf{a}^{m-1})^{T} $$ $$ \textbf{b}^{m}(k+1) = \textbf{b}^{m}(k) - \alpha \delta^{m} $$

Using these equations, we can now train any arbitrary neural network to learn some function from input to output. Getting to an acceptable level of accuracy will typically take several iterations of gradient descent over the entire input set (each full iteration is known as an epoch).

As a final clarification, backpropagation is the step of propagating the error terms backwards in the network. Gradient descent is the process of actually using these error terms to update the parameters of the network.

Optimization in Practice

Watch the following video for an introduction to further methods in optimization.

Although gradient descent is a super powerful tool, it isn’t without its flaws. Turns out, it may not always converge on the optimal parameters for our model: it may end up overshooting the optimal point, finding a local minimum of our cost function instead of the global minimum, etc. Thankfully, there’s a whole slew of optimization techniques that build upon gradient descent to allow our network to more intelligently minimize the cost function.

Regularization

The following video builds off the last video and introduces the concept of regularization.

Data is never perfect: our observations contain both signal (which reflects some real, underlying process), and random noise. If we make the model fit our observations too closely, we will end up fitting it to this noise as well, which will make for some pretty weird and unintuitive predictions.

In order to diagnose overfitting, we’ll hide a part of our observed data from the model (we’ll call this the test set), and only train our model based on the remaining data (we’ll call this the training set). Measuring our model’s performance on the test set will allow us to get an unbiased view of how well our model can make generalized predictions from unseen data, so if our test set cost is much higher than our training set cost, we can be fairly certain that our model has overfit the training data at the expense of generalized prediction ability.

Potential fixes for overfitting include getting more data (if possible), and using a technique called regularization. Regularization penalizes overly complex models by adding the squared-magnitudes of the model weights to the cost function, often resulting in smoother, more robust models that are more capable of making general predictions in the real world.

When we design a machine learning algorithm, the goal is to have the algorithm to perform well on unseen inputs. Regularization deals with this, allowing the model to perform well on the test set which the algorithm has never seen before, sometimes at the cost of the training accuracy. Regularization is the process of putting a penalty terms in the cost function to help the model generalize to new inputs. Regularization does this by controlling the complexity of the model and preventing overfitting.

Given a cost function \( J(\theta, \textbf{X}, \textbf{y}) \) we can write the regularized version as follows. (Remember \( \theta \) notates the parameters of the model). $$ \hat{J}(\theta, \textbf{X}, \textbf{y}) = J(\theta, \textbf{X}, \textbf{y}) + \alpha \Omega(\theta) $$ The \( \Omega \) term is the parameter norm penalty, and operates on the parameters of the network. In the video, this term was set to equal the sum of the squares of the weights in the network. The constant \( \alpha \in [0, \infty) \) (denoted using lambda in the video) controls the effect of the regularization on the cost function. This is a hyperparameter that must be tuned. The larger we make this hyperparameter, the more we will penalize larger weights, and the more "regularized" our model will become. Also, another note: when we refer to the parameters of the model in regularization, we typically only refer to the weights of the network -- not the biases.

Conclusion

If you made it through these past two lessons, you should hopefully have a good idea now of how the architecture of a neural network is set up, and how neural networks use their layers of neurons to gradually transform input data into a final prediction. (Remember: multiply inputs by weights, add it all up – including a bias, apply an activation function, and repeat.)

You should hopefully also have a general notion of how we go about training these neural networks, and also an idea of what challenges can arise during the training process. (For example, vanishing gradients, local minima, overfitting, etc.)

If some of the topics brought up in these last two lessons still don’t quite make sense to you, that’s perfectly ok. This material is pretty difficult for most people to pick up at first, but only gets better with patience and practice.

Now that you’ve built up a basic machine learning foundation, it’s time to let the real fun begin!

References

- http://neuralnetworksanddeeplearning.com

- http://hagan.okstate.edu/NNDesign.pdf

- https://www.amazon.com/Deep-Learning-Adaptive-Computation-Machine/dp/0262035618

- http://cs231n.github.io/

- https://jamesmccaffrey.wordpress.com/2013/11/05/why-you-should-use-cross-entropy-error-instead-of-classification-error-or-mean-squared-error-for-neural-network-classifier-training/